Trapezoids – An Argument for Inclusion

This piece has been adapted from a blog at StrongerMath.com

Picture a trapezoid. What comes to mind?

Does it look something like this?

That’s what trapezoids looked like to me, anyway. My teacher told me trapezoids have a pair of parallel sides, and every picture I saw in my textbook looked like this. I never really had a reason to question it any further. But one day, I started thinking about it a little more.

After all, we know what this shape is:

A square, of course! But none of us would bat an eyelash if someone called it a rectangle, because it meets all the rules for rectangles. It just has a little something extra.

And speaking of rectangles:

There it is. Two pairs of parallel sides and all. But wait, that means it’s also a parallelogram!

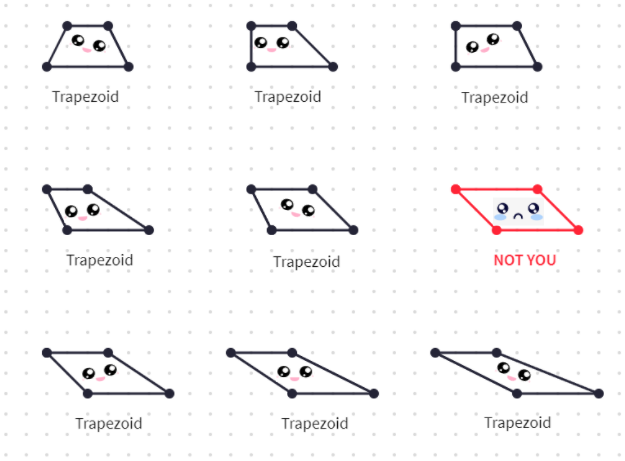

And while we’re on the topic of parallelograms, there’s this little cutie:

Who doesn’t love a rhombus? Or is it a kite? Oh, it’s all three!

We have no trouble accepting these multiple classifications for different quadrilaterals. But suggest that a trapezoid can have at least one pair of parallel sides instead of exactly one pair, and everyone loses their minds!

Unbeknownst to me, I had established what is sure to be a lifelong rivalry with Zak Champagne and wandered into a discussion that had been going on for some time: The Great Trapezoid Debate.

Camps had been established on opposing sides – those who defined trapezoids using an exclusive definition — a trapezoid has exactly one pair of parallel sides — and those using an inclusive definition — a trapezoid has at least one pair of parallel sides.

Now, you might not particularly have a firm opinion one way or another, and you wouldn’t be alone. And that’s totally okay! But I want to take a moment to talk about why (I think) this matters.

Math has a little bit of a reputation problem. It’s boring, it’s dry, there’s only one right answer or one right way of doing things. Everything is settled and nothing is up for debate. While the tides have started to turn a little bit, by and large this is still what comes to mind when most people think of math because this is what they experienced when they were in school.

Memorize this definition, use this algorithm, don’t ask questions.

The reality, however, is far more intriguing. Many of the things that we accept as fact in mathematics did not start out as universal truths. Equal signs, irrational numbers, negative numbers, even zero itself were up for debate until a collective agreement was reached, for one reason or another. Just recently, a fascinating conversation came up on Twitter about whether 0.999… is equal to one. I’m still not convinced that “convenience” is a good reason for zero to the power of zero to be equal to one instead of being undefined. But, I digress.

If we truly believe that our students are capable of being mathematicians and engaging with math authentically, then we also believe that they are capable of forming their own opinions and setting criteria that make sense to them and to others. Our job isn’t about building everything for students, but handing them the tools they need and offering guidance and encouragement. It’s about showing kids (and adults) that they, too, are able to examine evidence and come to a conclusion. It’s about demystifying a subject that has been exclusionary for far too long.

And that is why the Great Trapezoid Debate matters.

Written by Shelby Strong (@Sneffleupagus)