|

It was never just about the math, but always about the love

There are two quotes that I keep close to my heart and revisit before I begin teaching a math lesson. I don’t always say them, sometimes I recite them in my head less than perfectly, but they are always present in my actions and choices.

The first: “I have never encountered any children in any group who are not geniuses. There is no mystery on how to teach them. The first thing you do is treat them like human beings and the second thing you do is love them.” – Asa G. Hilliard III

The second: ““The teacher is of course an artist, but being an artist does not mean that he or she can make the profile, can shape the students. What the educator does in teaching is to make it possible for the students to become themselves.” – Paolo Freire

The first took me years to learn, to fully understand, and I confess that I am understanding what it means still in every interaction I have with a child on a learning journey.

The second is something I’ve felt in my marrow since I started this journey, this way of knowing and being that is in communion with younger souls and on their infinite possibilities. They are still unfurling, they are still growing and finding their own places in the sun. (and if I pause and reflect for more than a minute, so am I)

When I teach, I am in the forever nebulous terrain of learning, of wandering and wondering with my students.

Once upon a time, Robert Frost penned this poem:

Two roads diverged in a yellow wood,

And sorry I could not travel both

And be one traveler, long I stood

And looked down one as far as I could

To where it bent in the undergrowth;

Then took the other, as just as fair,

And having perhaps the better claim,

Because it was grassy and wanted wear;

Though as for that the passing there

Had worn them really about the same,

And both that morning equally lay

In leaves no step had trodden black.

Oh, I kept the first for another day!

Yet knowing how way leads on to way,

I doubted if I should ever come back.

I shall be telling this with a sigh

Somewhere ages and ages hence:

Two roads diverged in a wood, and I–

I took the one less traveled by,

And that has made all the difference.

I think about this in the context of mathematics – of pathways and pickings – that mathematics is not a well-trodden road, on which we set children to carefully and delicately follow. It is in the wildness of things we find possibilities for the most joy.

It is not a well-paved road, overseen by a monotonous guide intoning highlights in the driest of voices.

Mathematics is a finding. It is a gleaning. My job as head math witch is to show the magic of possibilities. Here – juicy berries burst delicately upon the tongue. There, look, a potential pathway.

But mostly, my job is to whisper softly “Observe. Look at the way the red cardinal flies. What do you find beautiful about it?” or to remark “Goodness, I am so proud of this glen we have stumbled across together, for we could not have found it without you.”

My job is to make the mundane sacred. There is a kind of holiness in exploration and all adventures alike. The delight of a first geometric construction or the hundredth.

The joy that follows – a shared basket of stolen apricots, a ripening, a mutual endeavor. I look for ways to make this happen – but, with all things, adventures are also not always pleasant; sometimes in the thorns and thickets of our explorations, we fail to find a pathway forward. We get frustrated with one another — what started off as a sunny excursion is full of biting horseflies, that despite our best attempts to wave them away, we cannot get rid of.

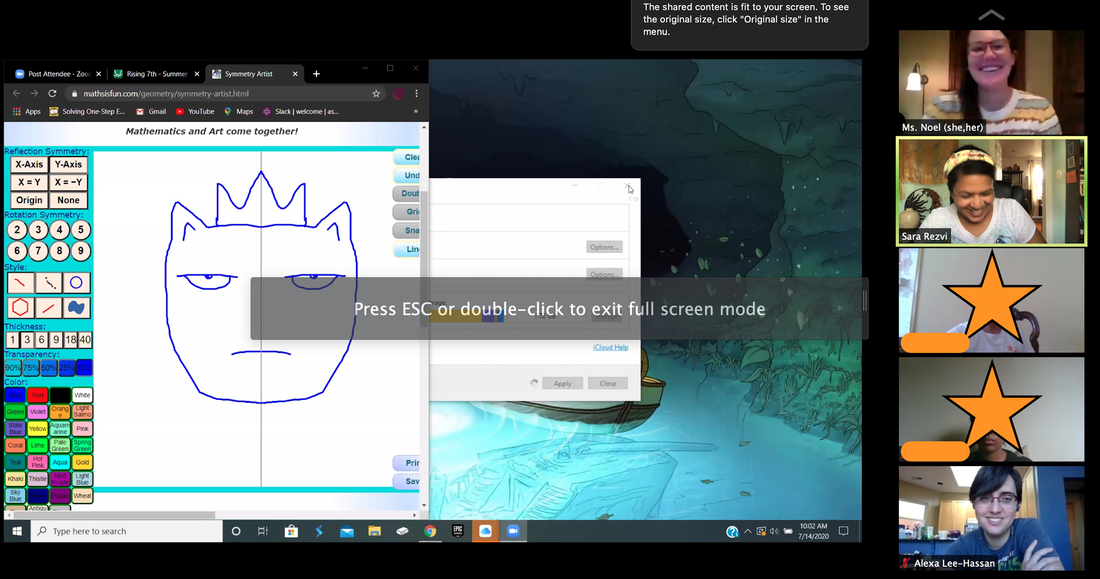

The adventure has changed now. We are in a new portal, trekking across a digital realm together. The world, which has not been safe or kind for so many already, especially for those that have been blessed by the sun’s kiss on their dark skin, has become even more precarious. An axis tilted ever further to its side. We who seek balance are spinning off-kilter.

So, within this topsy-turvy landscape, some questions must be prepared for, and planned for:

These are my essential questions when I set off upon a new journey. Each and every time:

- How do I love you as you explore? How do I demonstrate that love with kindness, with patience, with grace?

- How do I hold my hands, so golden brown these days, as footholds upon which you clamber? To make your own way?

- How do I show you that in failing, there is a lesson? One about yourself and the possible imaginaries of the world around you?

These are not quantifiable questions. They cannot be measured by standardized testing. They cannot be tied to funding. They cannot be visualized in sterilized graphs by those who have never set foot in an educational space.

…and yet they matter just the same.

~ Sara Rezvi (@arsinoepi)

|