|

Swimming in Water: Carceral Pedagogy in the Math Classroom

By: Lauren Baucom and Sara Rezvi

Poetry has a way of cutting to truth, of separating waves from the shorelines all the while observing both simultaneously. In his powerful poem, Guante notes that ‘white supremacy is not the shark, it is the water’. We swim in it, we are surrounded by it – these heady waters, this deep throbbing silence. Because of its constant presence, for many, it goes unnoticed, the water set as an unquestionable background. So, too, is the everpressing presence of carceral pedagogy in educational spaces. As writers of GMD, we refuse to participate in this silence. We mourn loudly. We bear witness deeply. We grieve. And we demand that these ideologies have no place within the mathematics classroom.

What is carceral pedagogy? How does it intersect with the mathematics classroom? What does it look, sound and feel like? Like the words of Guante, will we ever know it exists if we do not take time to recognize the waters in which we are constantly surrounded?

In a recent #Slowchat, Dr. Ilana Horn (@Ilana_horn) defined carcerality as “the physical domination and confinement of bodies in institutions, especially when they reinstate white supremacy.” Elsewhere, Dr. Bettina Love (@BLoveSoulPower), has discussed carcerality as systemic domination imposed by laws and enforced by incarceration. For the purpose of this piece, we define carceral pedagogy in the mathematics classroom to be the physical, mental, and social domination presented by the systems of white supremacy through laws, written and unwritten, that confine students’ bodies, minds, and spirits in the dehumanizing experiences of their mathematics education.

In this moment of virtual teaching when teachers have a voyeuristic ability to track, watch, and mandate policies through their surveillance apparatus of choice (ClassDojo, Zoom, Google Meets, etc), we’ve experienced how EduTwitter has taken the purpose of education as a source of liberation and used this time and space to incarcerate students’ minds and bodies through a system of compliance and oppression. Children are subjected to the ever-present disciplinary gaze of the carceral teacher. Some examples include: (1) when they can’t visit the bathroom in their own homes, (2) being forced to turn on cameras to be counted as present, and (3) being told not to eat in class when their caregiver offers them a snack. We must name these efforts of carcerality as they have quickly seeped into this new world of online learning during a pandemic. Rather than offering grace, compassion, and boundless love, carceral teachers have led the charge in creating spaces that invade privacy and invalidate the need to attend to growing bodies.

Simultaneously, we must revisit the mathematics classroom space of face-to-face teaching to understand how carcerality has been used in the past to oppress the bodies and minds of students.

In many classrooms, we have been sold the myth that students from low income areas require carceral style classroom pedagogy in order to succeed, and that without this type of oppression, they aren’t capable of doing the work. This kind of ideology is rooted in systems of white supremacy and dehumanization. We reject the narrative that the carceral teacher (who often is white) alone knows what is best for families and children of color. It is not the children that are lacking, but the carceral teacher.

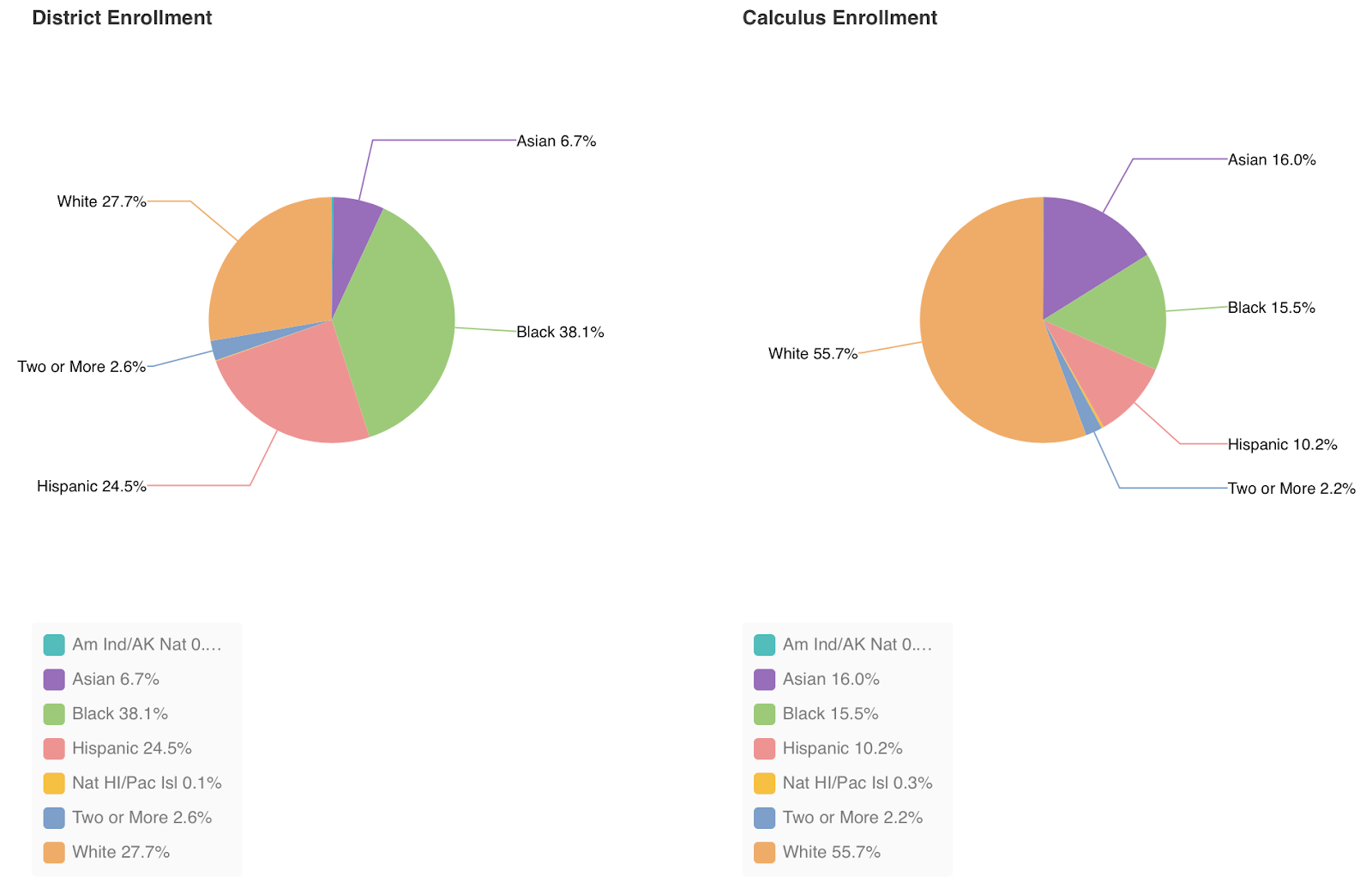

There has been much research to show how students of color, specifically Black girls, have been denied their right to joyfully belong in math spaces. Using the ocrdata.ed.gov site, we can find countless examples of the literal barriers that imprison students to classes that are unworthy of their brilliance. How is it possible that in a district where almost 4 out of 10 of the students enrolled are Black, that less than half are allowed entry into Calculus classrooms? What unwritten laws govern the body language of students who appear “deep in mathematical thought” versus those who are “lazy, unproductive, and unmotivated”, physically barring them from mathematical spaces? We find it interesting that these narratives begin for students of color at young ages and continue onward into adolescence, almost as if these ideas are baked into our societal consciousness – as if we are all swimming in it.

Carceral pedagogy is often thought of to be discipline-based classroom practice, but it is also curricular. With the constant reminder from textbooks that mathematics was created in Europe by White males and no one else, the lack of representation confines students’ minds and social identities. Texts such as Francis Su’s (@mathyawp) ‘Mathematics for Human Flourishing’ and Talithia Williams’ ‘Power in Numbers: The Rebel Women of Mathematics’ eloquently work to decenter this notion that mathematics has only ever been a Eurocentric endeavor rather than a Human one. Elsewhere, I (Sara) along with my co-authors, have argued that mathematics, just like literacy, needs to have its own set of windows, mirrors, and sliding glass doors.

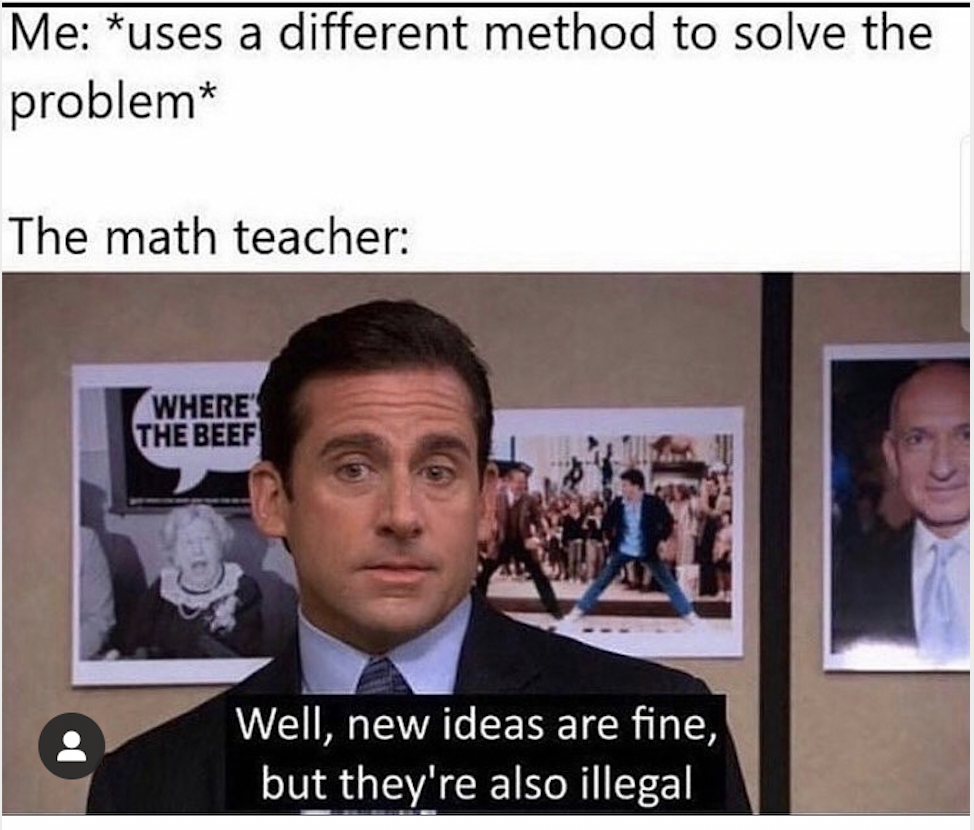

Another example of carcerality that appears in the mathematics curriculum occurs when a teacher requires a particular method of solving, rather than being open to the expansive, liberatory solving process that mathematics encourages.

Carceral classrooms are about control; when we try to control students’ thinking we create a low/no-trust environment with students that entraps their minds and eliminates the need for creativity, ingenuity, and authentic, original thought.

How is it that this meme can be so readily found when we describe math classrooms? That this concept of illegality in alternative thinking is synonymous with math classrooms, rather than the liberatory experience we know mathematics to be?

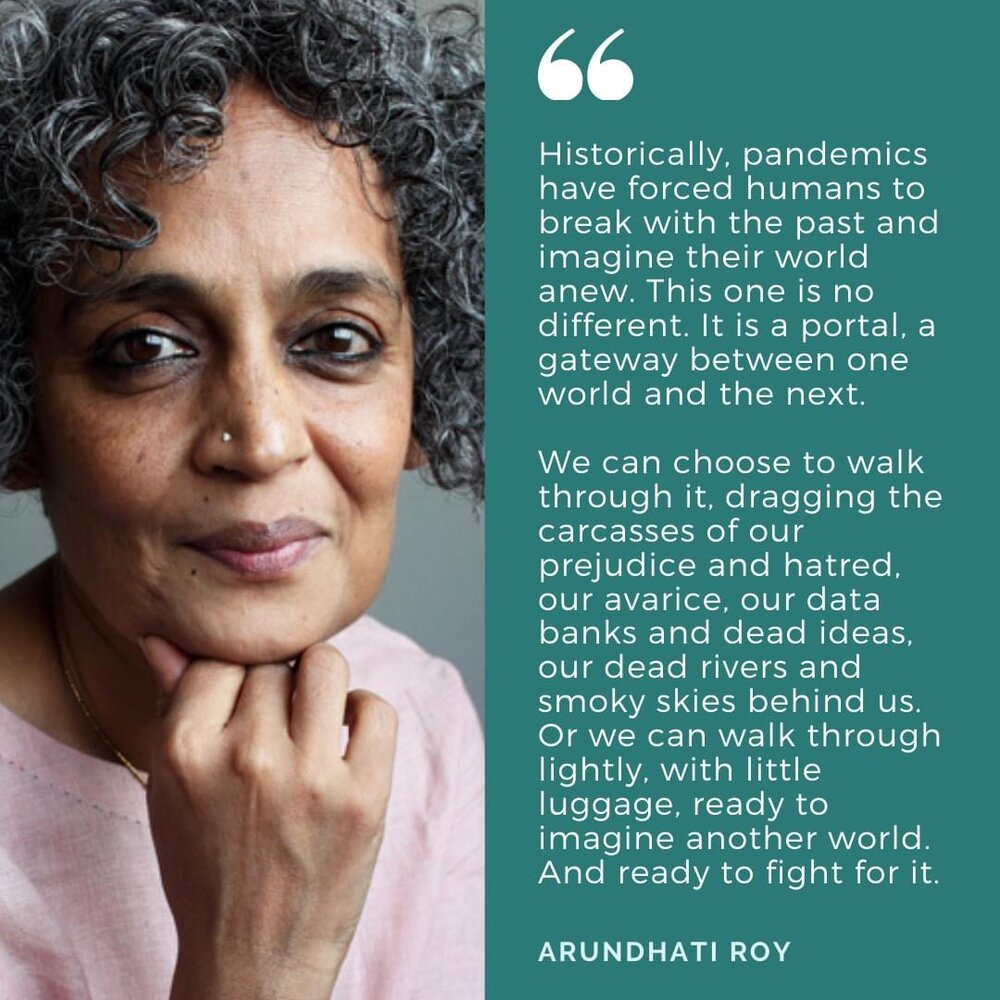

In closing, we reflect on the immediacy and urgency of Arundathi Roy’s quote. The pandemic is a portal. How we swim through it or whether we drown in it, is up to us. Where it leads to is up to us. We engage deliberately in the practice of freedom dreaming, of imagining a world beyond the violence enacted upon children in mathematics classrooms.

We are swimming in rough waters these days, full of murky sediment, glimpsing blearily into the unknown void. We have named here the silence, the complicity of holding onto dysfunctional systems that dehumanize children in the name of carcerality, of disciplinary productivity that seeks to mandate how we engage in mathematics (and beyond) as human beings. We ask the reader to consider the following – If we are more aware of the water, is that enough? Is our awareness enough? Do we keep swimming? Or do we change the scope of our navigations?

|