|

|

|

|

|

Online Professional Development Sessions

|

|

|

|

Tonight at 9:00 PM EST!

#DisruptiveNumbers, A Tool to Teach Mathematics for Social Justice

Presented by Bernadette Andres-Salgarino

Recommitting ourselves to teaching mathematics through the lens of social justice necessitates the reinvigoration of our pedagogical approach to learning. #DisruptiveNumbers is a tool to provoke mathematics discourse to unravel the intricacies that numbers bring to uncover hidden stories that perpetuate partisanship in our society. In this presentation, activities that use numbers and data in real-world contexts, and stories to bring awareness of sociopolitical issues that impact students’ lives will be shared.

To register for this webinar, click here.

|

|

|

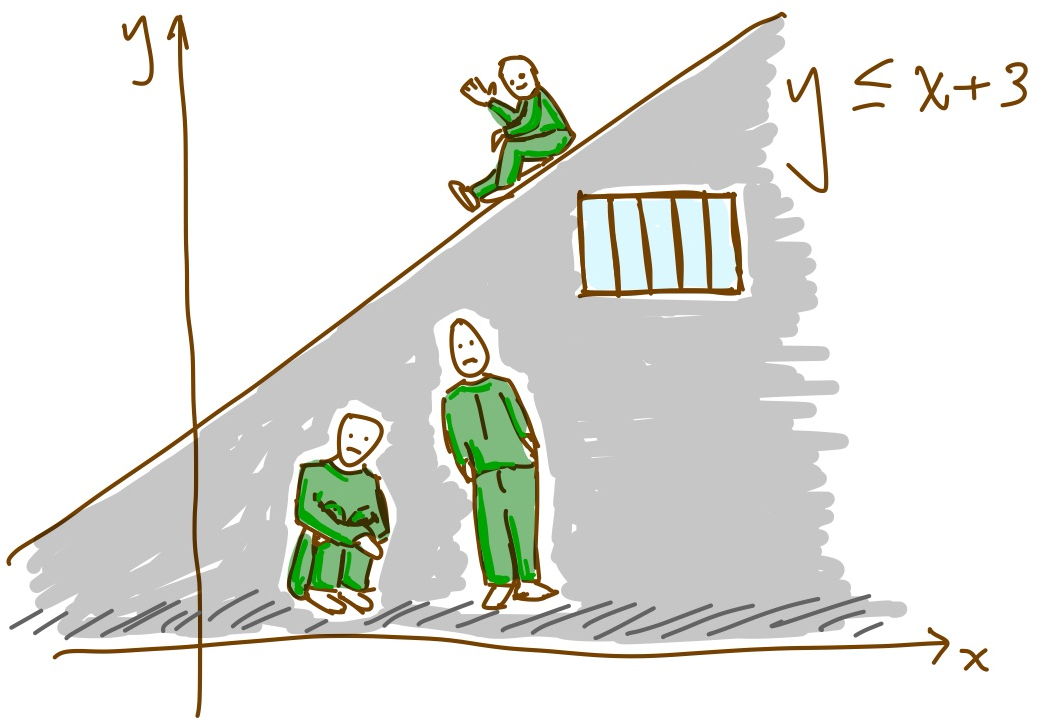

Liberatory Mathematics

for breaking out of jail

In 2019, I taught Contemporary Mathematics in a medium security men’s correctional facility. Prior to that experience, I had never been inside a correctional facility, nor had I had significant conversations with anyone who had been incarcerated. Following that experience, I started corresponding with inmates through the Prison Mathematics Project, and I am writing this piece with the following in mind.

- Through teaching and corresponding about math with incarcerated folks, I have uncovered a core principle of my teaching philosophy: “Everyone deserves to find freedom and joy in mathematics.”

- Incarceration and feelings of isolation while learning math create barriers to learning that are unique to the incarcerated

In my Contemporary Mathematics course, I had fully intended to give students my best active learning pedagogy in every class. But one day I arrived, waited with colleagues for almost 2 hours for correction officers to clear the instructors to go to our classrooms, and found an exhausted group of men. There had clearly been An Incident, and on a “normal” campus, I would have rescheduled our class. On this campus, rescheduling was impossible for logistical reasons, but also — my students wanted to be there, even exhausted, because our classroom was a different kind of space for them. Did we do the small group, active inquiry exercises I had planned? Reader, we did not. I covered some material with a (minimally) active lecture, and saved time at the end for just… sitting there. Doing math, not doing math, whatever.

“Every day that I wake up and go about my life I try not to allow the present circumstances that I’ve created for myself to determine the passions and the future I want to see myself in,” writes Christopher Jackson, an inmate whose correspondence with Francis Su inspired the book Mathematics for Human Flourishing. Su and other educators are working toward a vision of liberation while — and through — learning mathematics (see also @ATN_1863). This past summer, I attended a workshop on Embodying Liberatory Practices in the Classroom put on by the NYU Metro Center ( @metronyu). This workshop was important to my own continued growth as a professor for many reasons, but in particular, it gave words to a feeling that had been growing as I experienced and learned more about math in prison. It’s not just students in traditional classrooms who deserve liberation; math learners in prisons deserve a liberatory classroom, too.

To fully see our incarcerated students’ circumstances, we have to understand who is in prison. Given the demographics of the incarcerated in the US, rehumanizing mathematics and trauma-informed pedagogy are necessarily linked with liberatory mathematics in prisons. (In my 30+ years of being in classrooms as a learner or teacher, my Contemporary Math class had the most diverse group of students along the axes of age, ethnicity, and race.) But the math pedagogy that works for joyful, collaborative, community-oriented mathematics in “normal” classrooms doesn’t seem to translate neatly to prison. Barriers to learning combine in ways that are specific to being in prison; a pedagogy for teaching in prison must anticipate and respond to those.

What I felt then (and still feel now) is that there must be more to teaching in prison than just doing my best and adapting on the fly. There is surely a network of people who are thinking hard about mathematics education for incarcerated people. And they’re not just thinking about how classrooms are a place for incarcerated people to learn mathematics, but they’re thinking about how teaching and learning mathematics is a way to affirm the humanity of incarcerated folks. And I want in!

So, dear Global Mathematicians, I hope you’ll correspond with me about the following questions:

- Who is thinking through/has thought through/wants to think through math pedagogy specific to correctional facilities? How do we keep in touch?

- What body of literature is out there that can help support improvements to prison education programs (including but not limited to improvements to, e.g., the interested instructor)? How does the interested practitioner find resources and opportunities like The Inside Out Center?

What is our homework as abolitionists — keeping carceral pedagogy out of our schools, keeping folks out of prison, ensuring that classrooms and prisons are safe places for those who inhabit them, and increasing access to liberatory mathematics? How can we be effective together where we might be ineffective individually?

|

|

|

The Profession of Education

This last week, Christie Nold (@ChristieNold) posted a tweet that went viral. In the tweet she responded to the idea of educators working over the summer, noting that we are all exhausted. Being asked to do additional work, which most of us already are in these days of hybrid learning, only raises our own awareness of the fatigue we all feel as we try to simultaneously survive a pandemic and educate children.

The idea of students attending summer school is related to the new trend of discussing “learning loss”. For an excellent article on how the concept of “learning loss” is problematic, read this one by Julia Matthews. In it she states,

“The frame of ‘learning loss’ also highlights the flawed belief that learning is tightly bound to instructional minutes and synonymous with grading and testing. Yet meaningful learning is rarely “lost.” The imposed fear of falling behind on content delivery puts educators in an untenable position, and inserts a reductive version of school in the home.”

One thread that ties the exhaustion of teachers now and the made-up take on “learning loss” from the general public together is the deprofessionalization of educators. I wonder:

What would it take for education to be taken seriously as a profession?

In March, April, & May, teachers were heralded as heroes. In August, when they asked for safe working conditions and guidelines during a pandemic, we were told we were lazy and didn’t want what was best for kids. And now, in February, a year from when pandemic teaching began, we are exhausted and asked to make up gains for children in an imaginary standard in order to appease the general public. How can the professionalism of a career that many claim is so noble and consequential for society constantly be the target for others to denigrate?

- Is it because we don’t have a standardized process for measuring teaching professionally? Nope, we have that. (see National Boards for Professional Teaching)

- Is it because we need research that shows that teaching mathematics, knowing mathematics, and doing mathematics are inherently different sets of knowledge? Nope. We have that. (see Math Knowledge for Teaching from Ball, Thames & Phelps, 2008)

- Is it because we need a large social catastrophe that demonstrates the weight of the profession in general society? (See the ongoing global pandemic)

If we have all the receipts for our work, how come others readily choose to ignore it as such?

Sometimes, when I have more questions than answers, I go back and look at the receipts, especially the ones that come from the students. Fawn Ngyuen (@fawnpnguyen) posted yesterday asking teachers to share a comment that a student said that still makes you smile. The post brought me laughs, smiles, and a few tears. Thanks, Fawn.

Pandemically Pondering,

Lauren Baucom

@LBmathemgician

|

|

|

The Critical Ninth-grade Year: Learning and Grades in a Pandemic

I hated teaching 9th grade math until I loved teaching 9th grade math. Ninth graders have a lot of energy and innocence but most of all, they have curiosity about the world, about themselves and their peers, about growing up and becoming a part of the world, and some (few) were even curious about math. Ninth grade is a critical transition year for young people and more so if you’re Black, Indigenous, or a person of color (BIPOC); research backs this up even if it’s not surprising for any high school teacher who has worked for even one year in a working-poor public school.

This pandemic has me thinking a lot about 9th graders whose only experience in high school has been online, not having opportunities to connect with their peers, explore extra-curriculars and sports and all the other rites of passages that come with transitioning from elementary to secondary. And not to romanticize high school in any way because a part of going to high school at least in places like Chicago also involves not being academically prepared for the demands of high school, challenges involved with navigating a new bureaucracy with its own set of norms and regulations, increased freedom, and not the least of it all, class content that quite honestly feels largely irrelevant for teenagers.

While most high schoolers may not drop out during their 9th grade, students grades and GPA in that first year are consequential for graduating high school, college enrollment, and even college retention through the 1st year. In their research report, The Predictive Power of Ninth-Grade GPA, the Chicago Consortium on School Research (CCSR) lays out their methodology and key findings that show the impact of a ninth grader’s GPA on the aforementioned outcomes. In their study that draws on data from over 180,000+ students across 8 cohort of students in Chicago from 2008 to 2013, ninth-grade GPA is a strong signal of what’s to come years later. The short of it is that the more we can help ninth graders experience success in their courses and freshmen grades, the more likely they are to stay in school and do well. The research base largely done by CCSR over decades now in Chicago Public Schools, has led to a key metric labelled the Freshman-on-Track metric that measures the number of students in a given school who have accumulated at least 5 full-year course credits and no more than one F in a core class. This metric has catalyzed freshmen teachers, administrators, and support staff to hone in on the 9th grade year ramping up efforts to provide students with the necessary supports to meet the metric. Schools have created such things as Freshman seminars dedicated to making the tools and steps for success explicit for students, summer bridge courses for struggling incoming ninth graders, additional academic supports at the ninth grade, among others. A system-wide focus on improving the Freshman On-Track metric with coaching and professional development resources has resulted in sustained, system-wide improvement in graduation rates, college access, and college retention rates. The documentary The Second Window: How a Focus on Freshman Transformed a System details the research base for its success.

Given what I know anecdotally from having taught 9th grade math for over a decade, in light of the amassing research underscoring ninth grade as a consequential year for academic success has me thinking a lot lately about ninth graders’ remote experiences with even stronger anguish. And while the above research tells us that ninth-year grades are key, remote learning has presented us with a unique opportunity to rethink the purpose and ways of education. I’m not interested in ‘learning loss’ as much as making a call to all ninth grade teachers to take stock of our classrooms, our students and their families, and even our own families and communities in the current moment. Although I recognize that we, as teachers, hold ourselves to high standards for teaching content, we must remember that we teach children and then we teach content. Although I truly believe that teachers of all subjects are making space for students to make connections and are attempting, in their own creative ways, to address students’ social emotional needs, I want to offer two ideas from my experiences having taught ninth grade for others to (re)consider:

- Humanizing through Relationships: While not a new or unique idea, it is worth saying it again here: we have to find a way to humanize remote and hybrid spaces by placing relationships and students’ voices at the center. Whereas before we may have dangled grades and rules to try to get students to comply, it is clear that relationships and responsiveness could not hold a stronger imperative. This means that we may have to (if we have not already) let go of our press to teach as much content. We might even resurrect the Coalition of Essential Schools principle of ‘less is more’ here. If students are not engaged authentically, they are not really absorbing our lessons in any meaningful or enduring way. In order to engage students and meet them where they are at requires courage and vulnerability to put the textbook down and, yes, talk to our kids. Engage them in the current problem of teaching and learning, however you and your students co-construct it. By opening a mutual dialogue with students, you are offering them a space to co-author a solution that has more potential to actually be a solution, even if only temporarily, because the students created it. But know that students’ disengagement is not solely tied to remote learning as the pandemic has overwhelmed the kinds of supports that young people, families, and communities used to rely on in the past. This dialogue may raise issues that feel (and largely are) beyond our control. That is okay but sometimes just giving students the space to air their feelings and grief is an important step moving forward, building a community of connection. We must also find ways to celebrate our students, for their resilience, for their commitment to show up every day, and for simply being who they are.

- Learning and Grades: I would be remiss to not return to the Consortium research cited above that strongly correlates grades with future academic outcomes. While there have been recent calls to radically transform our grading practices now more than ever, there has been growing evidence for some time now to support the ways in which our current system is antiquated, inequitable and even mathematically inaccurate (Feldman, 2019). Undoubtedly, schools have probably seen more F’s on students’ report grades at every level forcing administrators and instructional leaders to rethink their pandemic grading practices and, in some cases, even hold back students’ grades due to lack of assessment evidence as students turn in less and less completed work. I’ll offer here an alternative and fluent grade that we created at the Young Women’s Leadership Charter School (YWLCS) in 2000 called the Not Yet which incidentally Carol Dweck mentioned in her Ted Talk on Growth Mindset in 2014. Each course at YWLCS was tied to 8-10 outcomes (majority content-based with few behavioral outcomes) for which each student was given a grade among Highly Proficient, Proficient, or Not Yet. The girls (it was an all-girls public charter school) had essentially up until their Senior year to make up their Not Yet grades which required them to work with the discipline-specific teacher to make a plan to work on the content and make it up. There were benchmarks put in place to ensure we were not setting them up to make it too far along without any Proficient grades, but, for example, I could be approached by a student in Algebra 2 wanting to demonstrate proficiency in an Algebra 1 concept or skill. I might quiz her right there on the spot or ask her to do an assignment to demonstrate her competency. If she demonstrated proficiency, I could and would go into the system and change the grade. While this might appear overwhelming (and it was), we learned to be assessment heavy changing our instructional practices and shifting our conversations with students from completing work to demonstrating proficiency. This was significant and should not go understated. Not only were students talking about and demonstrating content, they internalized the notion that learning is ongoing and is based on effort not ‘smartness’. This assessment system, or at least the concept of a Not Yet, could offer our current students (9th grade and otherwise) acknowledgement that we are going through a pandemic together and that we hold their social, emotional, and physical needs with the utmost regard. It is not that learning is not happening: we might even take stock of what we are learning and reassure ourselves that academic competencies will be learned, in due time.

Written by Patty Buenrostro

|

|

|

Get Involved with the Newsletter

Our team of writers and curators is committed to produce content that is reflective of our Statement of Solidarity and with the goal of moving these words into action.

With this in mind we are calling for new volunteers to expand our perspectives and raise our collective voices to move this publication forward. If you are interested in becoming a regular contributor or would like the opportunity to contribute as a guest writer, please fill out this form.

|

|

|

|

Research and GMD – Join the Study!

The Global Math Department and researchers at North Carolina State University are undertaking a study to learn about teachers’ learning experiences from participation in the GMD. You can participate in this study if you have participated in the GMD as a presenter, attendee of a GMD conference, or reader of the GMD newsletter.

We invite you to click the link to join the study as a participant and to learn more!

|

|

|

|

Check out past and upcoming Global Math Department webinars. Click here for the archives or get the webinars in podcast form!

You can also visit our YouTube Channel to find videos of past sessions and related content.

|

|

|

|

|

|

|